Treatment of Sam and Mam in Low- and Middle-income Settings a Systematic Review

- Review

- Open Access

- Published:

Treatment of severe and moderate astute malnutrition in low- and middle-income settings: a systematic review, meta-analysis and Delphi procedure

BMC Public Health book 13, Article number:S23 (2013) Cite this article

Abstruse

Background

Globally, moderate astute malnutrition (MAM) and severe acute malnutrition (SAM) bear on approximately 52 million children under five. This systematic review evaluates the effectiveness of interventions for SAM including the Globe Health Organization (WHO) protocol for inpatient direction and community-based direction with gear up-to-use-therapeutic food (RUTF), equally well as interventions for MAM in children under v years in low- and middle-income countries.

Methods

We systematically searched the literature and included 14 studies in the meta-analysis. Study quality was assessed using CHERG adaptation of Course criteria. A Delphi procedure was undertaken to complement the systematic review in estimating case fatality and recovery rates that were necessary for modelling in the Lives Saved Tool (List).

Results

Case fatality rates for inpatient treatment of SAM using the WHO protocol ranged from 3.4% to 35%. For community-based treatment of SAM, children given RUTF were 51% more likely to reach nutritional recovery than the standard care grouping. For the treatment of MAM, children in the RUSF group were significantly more than likely to recover and less likely to exist non-responders than in the CSB group. In both meta-analyses, weight gain in the intervention group was higher, and although statistically significant, these differences were modest. Overall limitations in our assay include considerable heterogeneity in many outcomes and an inability to evaluate intervention effects dissever from commodity event. The Delphi procedure indicated that adherence to standardized protocols for the handling of SAM and MAM should accept a marked positive bear on on mortality and recovery rates; notwithstanding, true consensus was not accomplished.

Conclusions

Gaps in our ability to estimate effectiveness of overall treatment approaches for SAM and MAM persist. In addition to further impact studies conducted in a wider range of settings, more loftier quality program evaluations need to be conducted and the results disseminated.

Introduction

Globally, approximately 33 million children under five years of historic period are afflicted past moderate acute malnutrition (MAM), defined equally a weight-for-pinnacle z-score (WHZ) between -2 and -3, and at least 19 one thousand thousand children under five by severe astute malnutrition (SAM), defined equally a WHZ of <-3 [i, 2]. For children with SAM, the adventure of death is approximately 10-fold higher compared to children with a z-score ≥ – 1 [iii]. Based on an analysis past UNICEF, WHO and the World Banking concern [2], 32 of 134 countries for which at that place was data on prevalence of acute malnutrition (WHZ <-2) had a prevalence of 10% or more – a threshold that represents a "public wellness emergency requiring firsthand intervention" [two]. This analysis too showed that, since 1990, prevalence rates of wasting (acute malnutrition, WHZ <-2) have declined iii times more than slowly than for stunting (chronic malnutrition, height-for-historic period z-score <-2), decreasing past eleven% and 35% respectively.

SAM inpatient management guidelines have been published by the World Health Organisation (WHO), and updates to the protocol are pending [one, 4]. Practitioners and WHO experts endorse community-based management for uncomplicated SAM while still advising that children who are severely malnourished and have medical complications, such as severe oedema, should be treated in an advisable health facility [one, 5]. With respect to the management of MAM, there are several published guiding documents [half dozen–8] and in that location is ongoing interaction amongst researchers, practitioners and policy makers; however, at that place is currently no standardized approach to the management of MAM.

Since the early on 2000s, the products used to evangelize nutrients for management of SAM and MAM and the approaches used to target and deliver these products have been evolving chop-chop. Innovations include new formulations and packaging and a shift from institutional to customs-based management. Particularly formulated foods are the cornerstone of treatment programs and include fortified composite foods (e.chiliad. corn-soy alloy (CSB)) likewise every bit ready-to-use-foods (RUFs). RUFs are nutrient-dense products that are formulated every bit lipid pastes, bars or biscuits that provide specified amounts loftier quality of protein, free energy and micronutrients, depending on the target population [9]. Detailed summaries of RUF types have been described elsewhere [vii].

Specific aspects of inpatient management of SAM, for case approaches to treating infectious, Iv fluid for shock, management of diarrhea in SAM and management of micronutrient deficiencies [10] also equally antibiotic use in SAM management [11, 12] accept been reviewed. Nonetheless, there has not been a systematic review of the WHO protocol in its entirety, compared to standard care. This is essential for understanding whether the protocol is effective equally a package. In 2008, a preliminary review of approaches to treat SAM was undertaken for the Lancet Maternal and Kid Undernutrition Series [13]; however, this review included more broadly defined cases of undernutrition, was not specific to children nether five years, and included trials of variable quality and methods.

Two recently published Cochrane reviews accept as well investigated specially formulated foods for treating children with MAM [14] and SAM [xv] and RUTF for habitation-based treatment of SAM in children six months to 5 years of historic period [15], and while the details of the analyses vary somewhat, the overall conclusions are congruous with the analyses presented hither. Other reviews of community-based management of SAM besides as direction of MAM have been conducted [16–18]; however, these reviews typically did not include meta-analyses and included studies using definitions of malnutrition, such as weight-for-age, which are not all specific to acute malnutrition.

We undertook a systematic review in lodge to evaluate the effectiveness of approaches to managing SAM, including the WHO protocol for inpatient management [iv] and community-based management using RUTF [five], likewise every bit the effectiveness of approaches to managing MAM. Our review focused on children under 5 in low- and middle-income countries. In addition, we aimed to identify gaps in the literature and to generate the effect estimates necessary for including these interventions in the Lives Saved Tool (LiST). List models the reduction in child deaths by specific causes associated with increasing coverage of individual interventions. Recent mortality rates and cause of decease data for newborns, infants, and children are incorporated, by country, using estimates established by the Child Health Epidemiology Grouping (CHERG) [19].

Methods

Searches

We developed comprehensive search strategies for the following databases: Medline, Embase, Web of Science, WHO regional databases and the Cochrane library (see additional file 1). We conducted hand searches for sources of grey literature, including the Emergency Nutrition Network and Epicentre websites, Grey Literature Review and the Globe Bank website. Nosotros also issued a telephone call to primal non-governmental organizations requesting reports from their programs.

Literature published after 1970 was included and nosotros did not restrict past language. Searches were conducted betwixt October 9, 2012 and November 3, 2012. We did non limit by study blueprint blazon or by publication type when selecting studies for inclusion. Notwithstanding, nosotros excluded before-and-later studies in the meta-analysis, as we were not confident in the abilities of these studies to isolate the intervention effect separately from the misreckoning variables.

We divers MAM as weight-for-top z-score (WHZ) between -2 and -3 standard deviations (SD), weight-for-height (WFH) 70-80% of the NCHS or WHO reference median or mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) of 115-125mm. We defined SAM as weight-for-acme z-score (WHZ) <-3 SD, weight-for-height (WFH) <70% of the median NCHS or WHO reference or mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) <115mm or oedema [4].

We contacted authors who used alternative definitions of astute malnutrition or in cases where there was insufficient data available in the publications to request additional information or disaggregated data. An asterisk next to the authors' names in the forest plots indicates the use of unpublished data.

Data synthesis and quality assessment

We coded and categorized the types of interventions in each article. For moderate acute malnutrition, we conducted a meta-analysis merely on set up-to-use-supplementary nutrient (RUSF) compared with CSB, as this was the only comparison with multiple studies that could be pooled. As well, for severe astute malnutrition, we conducted a meta-analysis on RUTF compared with standard therapy. No report has included true control groups using placebo or no intervention for ethical reasons. Nosotros likewise conducted a meta-analysis on ii studies comparing inpatient handling to ambulatory handling for children with SAM and MAM, likewise as a meta-analysis comparing locally-produced RUTF to imported RUTF for rehabilitation of children with SAM.

We included outcomes needed for LiST and those routinely used for program monitoring. These include: bloodshed, recovery rate (every bit defined by authors), relapse rate (as defined by authors), default rate, time to recovery, and modify in anthropometric measures such equally weight, superlative, MUAC and WHZ. Outcomes with more than i data point were included in the final analysis.

We used a standardized data abstraction class to collect information regarding study characteristics, descriptions of the interventions and comparisons, outcomes of interest and effects as well as quality of the studies. We assessed quality based on the CHERG adaptation of the GRADE technique at the private study level and at the consequence level [xx]. Studies were classified as loftier, moderate, low or very low quality. The quality of each study was assessed based on study design, methods and generalizability.

Quality cess at the outcome level was graded based on volume and consistency of the evidence, forcefulness of the pooled outcome and strength of statistical evidence based on the p-value. Levels of heterogeneity were assessed past visual inspection, looking for overlapping conviction intervals, and by the I2 value. An I2 value of >fifty% was considered to exist evidence of substantial heterogeneity.

The meta-analysis was conducted using RevMan 5.ii®. We applied generic inverse variance methods to all analyses and used a random effects model in all cases; summary estimates are presented as relative risk (RR) or mean divergence (MD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

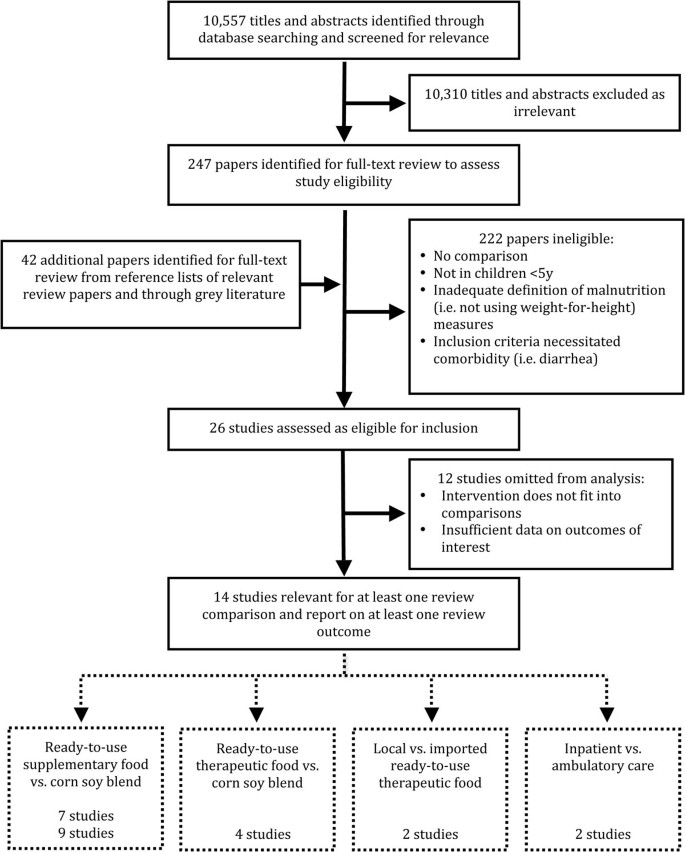

Our search identified ten,557 titles. Screening of these titles, full text review and data brainchild was done independently past two team members and then matched. Whatever disagreements were resolved through word or, where necessary, through consultation with a third team fellow member. After screening titles and abstracts retrieved by our search, 10 310 articles were excluded as clearly unrelated. The full-texts of 247 papers were screened and 26 papers were identified to encounter the inclusion criteria. Twelve studies were subsequently omitted from the meta-analysis as nosotros could not pool their interventions and/or there was insufficient data on whatever outcomes of involvement. A full of xiv studies were included in the concluding meta-analysis (run into figure 1).

Flow diagram showing identification of studies included in the review

The results accept been categorized by intervention blazon, and whether severe or moderate acute malnutrition was addressed. All of the trials were situated in areas of protracted food insecurity where wasting is owned. While prevalence of wasting will certainly respond to fluctuating environmental factors, none of the studies represented a situation of sudden and acute starvation. Forest plots for mortality, recovery charge per unit and weight gain are presented in the text; however, all wood plots can be found in additional file 2.

Customs-based management of severe astute malnutrition: Therapeutic feeding with RUTF vs. standard therapy

Three articles, representing two unique trials, were located that compared community-based direction with RUTF versus standard therapy in children with severe acute malnutrition [21–23]. Standard therapy entailed treatment in an inpatient facility until complications resolved, with the subsequent provision of Corn-Soy blend (CSB) for feeding the kid at home. Both were quasi-experimental trials gear up in Malawi. In one trial, all children were treated for infectious and metabolic complications in a nutritional rehabilitation unit; they were enrolled into the trial upon discharge and given either RUTF or CSB for home-treatment [21, 23]. The other trial enrolled children upon discharge from a nutritional rehabilitation unit as well equally direct from the community. All of the children in the standard therapy group and almost half of the children in the RUTF group had received inpatient handling [22]. The starting time did not test children for HIV, but presumably included a mix of children who were HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected and took place from 2002 to 2003 [22]. The other two articles reported data from the same trial, which took place in 2001. Ane reported data on the HIV-infected cohort [23], while the other reported information for children who were HIV-uninfected [21]. Nosotros assessed the quality of the studies equally moderate/low [22] and moderate/loftier [21, 23].

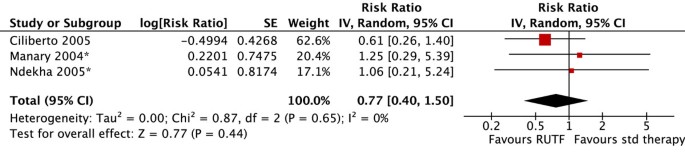

There were no meaning differences in bloodshed (figure two). Children who received RUTF were 1.51 times more likely to recover (defined as attaining WHZ ≥ -2) than those receiving standard therapy (RR: 1.51, 95% 1.04 to two.20) (effigy 3). There was substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 92%), the outcome was only marginally statistically significant, and this outcome was graded as low quality (come across table 1 for quality assessment). Children who received RUTF had a greater average height gain (MD: 0.14, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.22) and MUAC proceeds (Md: 0.11, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.18); both outcomes were graded equally moderate/low quality. Average weight gain in the RUTF group was also greater (MD: 1.27, 95% CI 0.16 to 2.38) and this effect was graded equally moderate quality (figure 4).

Forest plot for the effect of RUTF vs. standard (std) therapy on mortality in SAM

Forest plot for the effect of RUTF vs. standard therapy on recovery in SAM

Forest plot for the effect of RUTF vs. standard therapy on weight gain in SAM

Facility-based direction of severe astute malnutrition: WHO protocol for inpatient management of SAM vs. standard care

A literature review by Schofield and Ashworth [24] indicates that between the 1950s and 1990s, instance fatality rates (CFR) were typically 20-30% amid children treated for SAM in hospitals or rehabilitation units. Boilerplate CFR was higher (50-lx%) amid children with oedematous malnutrition. The persistence of high CFR was attributed to faulty case direction, and the authors called for prescriptive treatment guidelines as role of a comprehensive training program. In the 2008 Lancet Maternal and Child Undernutrition Series, the preliminary review estimated that treating children according to the WHO Protocol compared to standard care would result in a 48% reduction in deaths (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.43, 0.64) [13]. This was used in the model to decide touch on on mortality for SAM just requires refinement for the reasons mentioned in the introduction.

In terms of contempo studies, we found 1 before/after report [25], two retrospective chart reviews [26, 27], 1 quasi-experimental written report [28] and 4 prospective cohorts [29–33] that examined the case fatality rates and recovery rates of children with SAM treated according to the WHO protocol or an adapted WHO protocol. There was also one cluster RCT that compared inpatient treatment to home-care and solar day-intendance treatment [34, 35]; this report contained methodological issues and did not adequately describe the intervention (see additional file three for study cess).

None of the studies provided sufficient information to ensure that each step of the WHO protocol was followed and many noted variations from the protocol. One written report [31, 32] excluded children with severe complications and thus may not be generalizable. Case fatality rates ranged from three.4% to 35% (come across table ii). The highest CFR stemmed from a cohort of HIV-infected children [31, 32], while the lowest rate was accomplished in a study that provided few details on the protocol followed [34]. Only two studies provided data on recovery rates, which were 79.7% and 83.3%, respectively [28, 31, 32].

Ashworth noted that issues of training were paramount to improving outcomes, every bit bloodshed rates increased with the influx of new, untrained doctors into a hospital [29]. Two additional observational studies documented that implementing changes to dietary and clinical direction did non seem to be sufficient to promote substantial reductions in case fatality rates. Primal factors associated with improved outcomes were related to quality of intendance and institutional culture, including staff morale, attentiveness of nurses and support structures at the managerial level [36, 37].

Customs-based direction of moderate acute malnutrition: Supplementary feeding with RUSF vs. CSB

Our review identified v studies investigating the effect of Set-to-Use Supplementary Food (RUSF) compared to Corn Soy Blend (CSB) in moderately malnourished children under five years of age [38–42]. Two of the studies were cluster randomized controlled trials (cRCTs), one ready in 10 health centres and health posts in the Sidama zone of Federal democratic republic of ethiopia [39] and the other in the Dioila health district in Mali [38]. Three of the studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Ii were located in southern Republic of malaŵi [40, 41], and one in the Zinder region of southern Niger [42]. Two studies took identify from 2007 to 2008 [38, 42]; the remaining 3 studies took place during 2009 and 2010 [39–41]. We assessed the quality of the studies to be depression [42], moderate [38], moderate/high [39, 40] and high [41] quality (see boosted file 3).

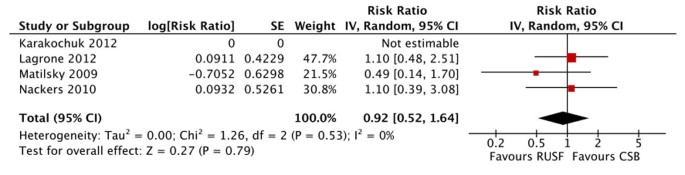

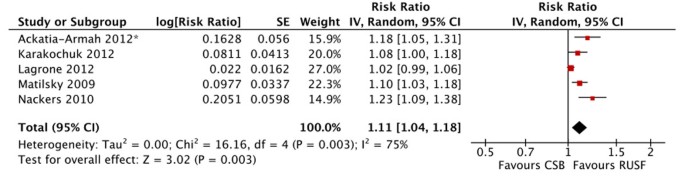

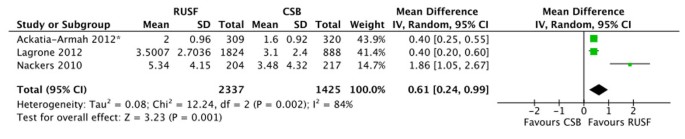

At that place were no significant differences in mortality for children given RUSF compared to those who received CSB (figure 5). However, the non-response charge per unit was significantly lower in the RUSF group (RR: 0.65, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.90). This issue has considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 57%) and was graded as moderate quality (see table 3). Children in the RUSF grouping were as well significantly more than likely to recover (RR: 1.eleven, 95% CI i.04 to ane.18), although this guess contained substantial heterogeneity and was graded equally moderate/low quality (figure 6). The rate of height gain did not differ between the intervention and comparison groups. Children who received RUSF had an average MUAC gain of 0.04 mm per day (MD: 0.04, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.07) and had an average weight proceeds of 0.61 g/kg/d higher (MD: 0.61, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.99) than those who received CSB (figure 7). Upon discharge or completion of the written report, children who received RUSF had an average weight-for-height z-score that was 0.xi z-scores greater than those who received CSB (MD: 0.eleven, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.17). While this is statistically significant, it may not be a sufficient divergence to be clinically important. Nackers et al. [42] followed-up with children vi months post-intervention. There were no significant differences in sustained recovery (defined as maintaining WFH ≥ 80% of the NCHS median post-treatment) or height gain.

Wood plot for the issue of RUSF vs. CSB on mortality in MAM

Forest plot for the effect of RUSF vs. CSB on recovery in MAM

Wood plot for the effect of RUSF vs. CSB on weight proceeds in MAM

The comparison groups in ii of the studies used standard CSB [39, 41]. 2 of the studies used "CSB++", which contains a revised micronutrient profile and contains higher quality poly peptide through the add-on of milk powder [38, 40] and the final written report used "CSB-based pre-mix", which contains additional oil and saccharide [42]. Nosotros performed a sensitivity assay, separating out studies using improved CSB (CSB++ and CSB-based pre-mix) from those using standard CSB. For mortality, the two studies using improved-CSB slightly favoured the comparison grouping, while the written report using standard CSB favoured the intervention group. For the rate of height gain, there is a very slight deviation in the direction of effect, but again there was no pregnant difference between the subgroups. The remaining outcomes showed consistent directions of outcome. There were no significant differences between the subgroups for any outcomes.

Severe acute malnutrition: Local vs. imported RUTF

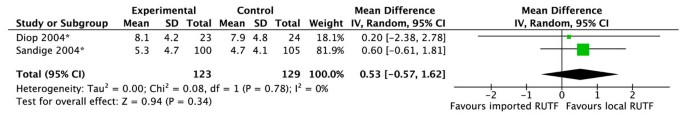

Ii trials, ane in Senegal, graded as depression quality [43] and the other in Malawi, graded as moderate quality [44], compared imported RUTF to locally produced RUTF used in community-based management of SAM. There was no significant difference in weight gain between intervention groups (figure 8). This effect was consistent (I2 = 0%) and the overall issue was graded every bit moderate/low quality.

Wood plot for the upshot of local vs. imported RUTF on weight gain in SAM

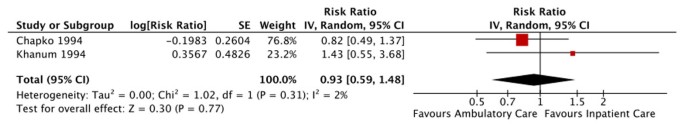

Severe and moderate acute malnutrition: Inpatient vs. ambulatory care

Two studies compared abode-based treatment to inpatient handling in children without severe complications. 1 moderate quality study in Niamey, Niger, enrolled children with MAM and SAM who were about to exist discharged from the hospital [45]. The other study, graded every bit low quality, allocated children presenting to the nutrition unit in Dhaka, Bangladesh, to receive either home-based or inpatient care [35]. A tertiary arm of this trial, 24-hour interval care, was non analyzed considering it could not be pooled.

In that location was no meaning difference in mortality between home-based or inpatient intendance (effigy 9). However, the studies produced contrary directions of upshot and the overall quality of this consequence was rated as very low due to problems with study design, analysis and availability of cardinal written report details (table 4).

Forest plot for the upshot of impatient vs. ambulatory care on bloodshed in SAM

Results from additional studies not included in meta-analysis

We identified several interesting singular studies that could not be pooled in the meta-analysis. Oakley et al. [46] studied the effect of an RUTF consisting of 25% milk versus some other with 10% milk in treating children with SAM, and constitute that the RUTF with the higher milk content was associated with a statistically significant college recovery rate (p<0.05). A trial in urban Senegal randomized children with SAM and MAM to receive RUTF or F100 (a therapeutic milk-based product used for nutritional rehabilitation in inpatient facilities) [47]. The report institute a statistically meaning difference in the rate of weight gain: children who received RUTF gained an average of 5.l g/kg/d more than than those receiving F100 (Dr.: 5.50, 95% CI 3.00 to 8.00). Branger et al. [48] investigated the consequence of adding spirulina, a microscopic algae to standard handling or standard treatment plus fish for children with moderate and severe malnutrition in Burkina Faso. The authors found no meaning differences betwixt handling groups.

Navarro-Colorado [49] found no significant differences in elapsing of rehabilitation or weight gain in children with astringent acute malnutrition randomized to receive F100 or BP100, a ready-to-employ food in biscuit course, although children receiving BP100 had a significantly higher energy intake. Finally, a double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled efficacy trial investigated the effect of adding probiotics and prebiotics to RUTF compared to standard RUTF. The study found no meaning difference in the primary outcome, nutritional recovery, or any of the secondary outcomes, including bloodshed. HIV-infected children were at a higher adventure of expiry in both groups, but HIV did not confound or modify the not-statistically meaning effect of the intervention [fifty].

We found very few rigorous trials that compared the provision of therapeutic or supplementary foods to other types of interventions aimed at modifying the upstream factors that contribute to the development of wasting. Fauveau [51] compared education on advisable complimentary feeding to instruction plus supplementary feeding in children aged 6-12 months. The supplementary food package contained rice, wheat, lentil power and cooking oil. While the grouping receiving the supplemental feeding package had a significantly higher monthly weight gain at three months, this issue was non sustained at six months of follow-up.

A new randomized controlled trial comparing RUTF to RUTF plus antibiotics (either amoxicillin or cefdinir) in children with simple SAM in an outpatient setting establish that the mortality rate was significantly higher in children receiving placebo than either antibiotic arm (amoxicillin RR: i.55, 95% CI 1.07-2.24; cefdinir RR: 1.lxxx, 95% CI 1.22-ii.64) [52]. The proportion of children who recovered was significantly lower among the placebo arm compared to either antibiotic arm (amoxicillin: 3.6%, 95% CI 0.6-6.7; cefdinir: v.eight% lower, 95% CI 2.8-eight.vii), with no pregnant differences in expiry or recovery between the two antibiotic artillery. Rates of weight gain among children who recovered were higher in the antibiotic arms compared to the placebo arm. HIV condition was not known for over half of the children in the study. Additional studies are needed to strengthen the evidence base of operations on whether children with elementary SAM should be provided routine antibiotics.

The Delphi process for establishing adept consensus

Our review constitute express loftier quality comparative trials evaluating the package of care offered through customs-based direction for uncomplicated SAM and MAM. Additionally, studies of inpatient management of SAM comparing the WHO protocol to standard intendance tend to exist observational without adjustment for confounding. Given the types of studies available and varying contexts for many of these studies, we complemented the systematic review with a Delphi procedure. The purpose of the Delphi practice was to gather and synthesize adept stance around the plausible touch estimates of interventions in diverse settings [53]. We invited both researchers and practitioners who are experts in SAM and MAM to participate and provided each adept with summary data from our systematic review, details about LiST, likewise as specific instructions for the Delphi process.

The Delphi consisted of three rounds. In the outset circular, we asked experts to provide their best estimates of CFR and recovery rate for inpatient and community direction of SAM. We also asked for CFR and recovery rate for 'optimal management' of MAM and asked each proficient to provide his or her opinion on which components institute optimal direction of MAM.

Nosotros calculated the arithmetic mean and range for each outcome and undertook thematic analysis of the qualitative data. In the second round nosotros provided each expert with the means and ranges of each estimate, likewise equally a summary of the themes for optimal management of MAM. Experts were given the opportunity to refine their indicate estimates and to comment on the summary paragraphs. In the third circular, we requested terminal comments or edits on the Delphi sections presented in this paper, and asked whether the experts wished to be best-selling in this newspaper.

Results from Delphi process

We received replies from 15 participants in round 1 (83%) and 13 participants responded to circular 2 (72% of full, 86% of circular 1 participants). All participants provided input on what constitutes 'optimal care' of MAM; thirteen participants contributed to the bloodshed and recovery rates in each circular.

For inpatient treatment of complicated SAM co-ordinate to the WHO protocol, the panel of experts gauge a CFR of fourteen% (range: 5-30%) and recovery rate of 71% (25-95%). The lower jump of the recovery rate is 25% results from one expert who expressed that a large proportion of admissions would default earlier recovery is reached. For customs-based treatment of SAM, the CFR was estimated at 4% (range: 2-seven%) and a recovery rate was estimated at eighty% (range: 50-93%). The bloodshed rate for MAM based on optimal treatment proposed by the experts (see additional file four) was estimated at 2% (range: 0-4%) and recovery rate was 84% (50-100%).

It should be noted that true consensus in estimating CFRs and morality rates was not achieved through this process, as a few participants did not provide a single estimate for each outcome, stating that the intervention furnishings varied considerably by context. There was a convergence of ideas around the general approach to managing MAM, as illustrated past the major themes described in boosted file four. Consensus was not achieved regarding whether all children with MAM (in areas of loftier HIV prevalence) should be screened for HIV, the relative importance of each component of the management approach, or the ideal form of nutrient to provide (whether in that location are other foods that are every bit effective as RUSF).

Word

The purpose of this review was to evaluate the effectiveness of approaches to treating SAM, both the WHO protocol for inpatient management and customs-based management using RUTF, likewise as the effectiveness of approaches to managing MAM. In all cases nosotros institute fewer high quality studies than expected. We were unable to conduct a pooled analysis comparing the bear upon of the WHO protocol vs. standard care for the treatment of SAM due to the blazon of studies bachelor. We conducted meta-analyses for community-based management of SAM likewise as management of MAM; however, for the MAM analysis, the information bachelor just allowed us to pool studies comparison ii food commodities. Thus, we were unable to adequately evaluate the intervention furnishings separate from product effectiveness. While there are limitations to both the review and Delphi process that will be discussed subsequently, the estimates generated from the literature review and later vetted through the Delphi process represent the side by side step in modeling interventions to accost SAM and MAM in Listing.

The WHO protocol for the inpatient direction of SAM is substantiated through considerable testify, based both in research and adept opinion [i, 54]. Several studies have demonstrated that information technology is possible to attain low CFRs. However, every bit illustrated by the lack of loftier quality intervention studies, lack of adjustment for misreckoning variables in observational studies, and absence of key details in many publications, there is a clear need for further research to improve our understanding of how to consistently achieve low CFRs across varying resource-constrained settings.

The shift to outpatient treat the treatment of simple SAM represents a major turning point in the management of severe acute malnutrition, as is has facilitated improved coverage and lower opportunity costs to caregivers [55]. Community-based management of severe acute malnutrition is backed by a wealth of observational and programmatic information [55–57], yet we found fewer impact studies than expected. While no significant deviation in bloodshed was found in our meta-assay, children given RUTF were 51% more likely to attain nutritional recovery in a timely manner, though there was substantial heterogeneity. The differences in anthropometric outcomes, while statistically significant, were small and may non be clinically meaning.

It should be noted that these pooled estimates were based on two cohorts of children, both in Republic of malaŵi, and thus may not be generalizable. Additionally, HIV is an of import factor to consider given that the HIV prevalence rate of children with SAM in Sub-Saharan Africa is loftier [58]. Unfortunately we were unable to disaggregate the meta-analysis every bit simply one trial tested for HIV. A 2009 review that included children with SAM concluded that HIV-infected children are significantly more probable to die than HIV-uninfected children, but used a broader definition of acute malnutrition [58]. Much remains unclear almost how to treat HIV-uninfected children with SAM [59].

The results of our meta-analysis on customs-based handling of MAM demonstrate that RUSF is slightly more benign than CSB. Although statistically meaning, the higher rate of weight in the RUSF group is minor and may not be clinically important. Children in the RUSF grouping were significantly more probable to recover and less likely to exist non-responders. However, these estimates contained considerable levels of heterogeneity, both in terms of written report design and in terms of intervention quality, which is poorly captured by most studies. Furthermore, several private studies that we were unable to pool in our meta-analysis report modest or no statistically significant deviation in primal nutritional outcomes when comparing products [sixty–62]. At that place are several dozen ongoing or planned studies focused on demonstrating efficacy or effectiveness between or amidst a range of possible food products and food supplements in the context of the management of MAM, well-nigh of which volition accept reports in the upcoming few years (personal communication CMAM Forum, 2012).

There are several limitations of this analysis. As some of the participants in our Delphi process indicated, outcomes of treatment programs are highly context specific and depend on groundwork rates of HIV, seasonal fluctuations in food availability, and many other context-specific variables. Additionally, the outcomes of the programs depend non only on the products used, but the general quality of the program pattern and implementation, as has been noted by several researchers [sixteen, 63–65]. Despite the importance of context, intervention quality, and the linking of inpatient and outpatient treatment programs along with preventive strategies, information technology was not possible to undertake a disaggregated analysis by context, due to the limited number of trials available, the lack of item given on the interventions and analysis in many studies, and the requirement for a unmarried effect gauge in LiST.

Further to the problems inherent in the analysis, there are issues with individual studies that warrant word. The diets given to children were often not described in detail, and the amounts of CSB given to the comparison group varied, sometimes including enough to share with family members. Thus dietary intake of study participants is non clear in all cases. Furthermore, all only one of the studies in the meta-analysis were conducted in Africa, with a bias towards Malawi (see additional file 2), thus limiting the generalizability of the results. Additionally, all studies passively recruited participants who were brought to treatment facilities. This may introduce bias if there are systematic differences between caregivers who are more likely, and those who are less likely, to bring their children to facilities for handling.

Directions for futurity research

Our review was unable to utilize a substantial proportion of studies due to inconsistencies in admission criteria, variability in the definition of acute malnutrition (including the apply of weight-for-historic period to assess nutritional status), and irregularities in how information is reported. In lodge to strengthen our understanding of the effectiveness of interventions, through the use of meta-assay, there should exist standard example definitions and reporting of outcomes at standardized fourth dimension intervals. Access criteria should be based on the WHO definition of astute malnutrition, or children meeting these criteria should be presented in a disaggregated analysis.

Farther high quality bear upon studies of approaches to managing SAM and MAM are needed. Particularly studies that reflect a broader range of settings where these weather condition are prevalent, including a range of geographic locations and areas with different illness prevalence (i.e. HIV). Though this area of research can present challenges for intervention studies, in that location are study blueprint options and data analysis techniques that allow for high quality inquiry. Where randomized controlled trials are not feasible, another selection would be to utilize a stepped-wedge design for research on customs-based management of SAM or MAM.

Our meta-assay was constrained with respect to the types of outcomes we were able to pool. Length of stay, relapse (requiring re-access to the hospital), default rate, sustained recovery and cost-effectiveness were not routinely measured, but are essential factors to consider in program planning. Furthermore, all simply i of the studies included in this review follow children for a relatively short period of fourth dimension, providing footling insight into long-term effects. A contempo follow-up study by Chang et al. [66] found significant differences in sustained recovery over 12-months of follow-upwardly, depending on the treatment given. Of all children successfully treated for MAM, sustained recovery was significantly more likely in those treated with soy/whey RUSF compared to those treated with either soy RUSF or CSB++; however, the authors ended that all children in the study remained vulnerable. More follow-up studies are needed to illuminate long-term effects on developmental outcomes, stunting, and the transition back to a home nutrition. Standardized follow-up intervals over a longer time period, and reporting on a wider range of outcomes would allow for college quality meta-analyses and a more than robust agreement the intervention effects.

Similarly, trials are needed to compare unlike approaches for the direction of MAM that consider local context, equally a one-size-fits all approach is not appropriate [67]. While food supplementation is necessary in humanitarian emergencies and chronic food insecurity, acute malnutrition is not bars to situations of conflict or famine [68]. In relatively more than stable situations, further inquiry is needed on preventive approaches that address upstream determinants of acute malnutrition, illustrated by the range of ideas brought along in the Delphi exercise (see additional file 4).

As the body of literature grows, it will also be important to disaggregate meta-analyses co-ordinate to context. Therefore, greater geographic representation is needed, as are studies designed to explore the impact of factors that likely bear upon the individuals' treatment outcomes, such as HIV status and household nutrient insecurity, as well as studies that are designed to tease out the elements of successful programs, beyond the option of commodity.

Conclusions

The paradigm shift towards community-based treatment of SAM has transformed the approach to treating acute malnutrition. Community-based handling is backed past substantive programmatic evidence; however, there are articulate gaps in the availability of well-designed studies evaluating the effectiveness of interventions to manage SAM and MAM in a range of contexts. Thus, establishing outcome estimates for Listing proved challenging. The meta-assay demonstrates some positive furnishings of the use of RUTF in comparison to CSB for the treatment of SAM or MAM in the community; yet, the effects were by and large small-scale and several outcomes had substantial heterogeneity. Meanwhile, the results of the Delphi signal that the use of standardized protocols for treating complicated SAM, simple SAM, and MAM, should lead to low bloodshed and high recovery rates. To close the gap between research and do, further studies are needed that compare approaches to managing SAM and MAM, taking local context into consideration.

References

-

WHO: Guideline update: Technical aspects of the direction of severe acute malnutrition in infants and children. 2013, Geneva: Globe Health Organization

-

Bank U-Westward-TW: Levels and Trends in Child Malnutrition: UNICEF-WHO-The Earth Bank Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates. 2012, Washington D.C

-

Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, de Onis G, Ezzati M, Mathers C, Rivera J: Maternal and kid undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet. 2008, 371 (9608): 243-260. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-0.

-

WHO: Guidelines for the inpatient handling of severely malnourished children. 2003, South-East asia Regional Office: World Health Organization

-

WHO: Community-based management of severe acute malnutrition: A Joint Statement past the Globe Health Organization, the Globe Food Plan, the Un System Standing Committee on Nutrition and the United Nations Children's Fund. 2007, Globe Wellness System

-

WHO: Technical note: Supplementary foods for the management of moderate acute malnutrition in infants and children 6-59 months of age. 2012, Geneva: World Health Organization

-

Taskforce UM: Moderate acute malnutrition: A decision tool for emergencies. 2012, UNICEF

-

WHO/UNICEF/WFP/UNHCR consultation on the management of moderate malnutrition in children under five years of age. Food Nutr Bull. 2009, 30 (three Suppl):

-

de Pee S, Bloem MW: Current and potential office of specially formulated foods and food supplements for preventing malnutrition among 6- to 23-calendar month-erstwhile children and for treating moderate malnutrition amongst 6- to 59-calendar month-erstwhile children. Food Nutr Bull. 2009, 30 (iii Suppl): S434-463.

-

Picot J, Hartwell D, Harris P, Mendes D, Clegg AJ, Takeda A: The effectiveness of interventions to treat severe astute malnutrition in young children: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 2012, xvi (xix): 1-316.

-

Alcoba G, Kerac M, Breysse Due south, Salpeteur C, Galetto-Lacour A, Briend A, Gervaix A: Do children with simple severe astute malnutrition need antibiotics? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS 1. 2013, viii (1): e53184-ten.1371/journal.pone.0053184.

-

Lazzerini M, Tickell D: Antibiotics in severely malnourished children: systematic review of efficacy, safety and pharmacokinetics. Balderdash Globe Wellness Organ. 2011, 89 (viii): 594-607. x.2471/BLT.x.084715.

-

Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Blackness RE, Cousens S, Dewey K, Giugliani E, Haider BA, Kirkwood B, Morris SS, Sachdev HPS, et al: What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. Lancet. 2008, 371 (9610): 417-440. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61693-vi.

-

Lazzerini G, Rubert Fifty, Pani P: Specially formulated foods for treating children with acute moderate malnutrition in low- and eye-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013, 6: CD009584-

-

Schoonees A, Lombard M, Musekiwa A, Nel Due east, Volmink J: Ready-to-apply therapeutic nutrient for domicile-based treatment of severe acute malnutrition in children from half dozen months to five years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013, 6: CD009000-

-

Ashworth A: Efficacy and effectiveness of community-based treatment of severe malnutrition. Food Nutr Bull. 2006, 27 (3 Suppl): S24-48.

-

Gera T: Efficacy and rubber of therapeutic diet products for home based therapeutic nutrition for astringent astute malnutrition a systematic review. Indian Pediatr. 2010, 47 (8): 709-718. 10.1007/s13312-010-0095-1.

-

Ashworth A, Ferguson East: Dietary counseling in the management of moderate malnourishment in children. Food Nutr Bull. 2009, 30 (3 Suppl): S405-433.

-

Winfrey W, McKinnon R, Stover J: Methods used in the Lives Saved Tool (List). BMC Public Health. 2011, 11 (Suppl 3): S32-10.1186/1471-2458-11-S3-S32.

-

Walker North, Fischer-Walker C, Bryce J, Bahl R, Cousens S: Standards for CHERG reviews of intervention effects on child survival. Int J Epidemiol. 2010, 39 (Suppl ane): i21-31.

-

Manary Mj, Ndkeha MJ, Ashorn P, Maleta Grand, Briend A: Dwelling house based therapy for severe malnutrition with prepare-to-employ food. Arch Dis Child. 2004, 89 (half dozen): 557-561. 10.1136/adc.2003.034306.

-

Ciliberto MA, Sandige H, Ndekha MJ, Ashorn P, Briend A, Ciliberto HM, Manary MJ: Comparison of home-based therapy with ready-to-use therapeutic nutrient with standard therapy in the treatment of malnourished Malawian children: a controlled, clinical effectiveness trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005, 81 (4): 864-870.

-

Ndekha MJ, Manary MJ, Ashorn P, Briend A: Dwelling house-based therapy with prepare-to-use therapeutic food is of benefit to malnourished, HIV-infected Malawian children. Acta Paediatr. 2005, 94 (2): 222-225. x.1080/08035250410022503.

-

Schofield C, Ashworth A: Why accept mortality rates for severe malnutrition remained so high?. Balderdash World Health Organ. 1996, 74 (2): 223-229.

-

Bachou H, Tumwine JK, Mwadime RK, Ahmed T, Tylleskar T: Reduction of unnecessary transfusion and intravenous fluids in severely malnourished children is not enough to reduce mortality. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2008, 28 (1): 23-33. 10.1179/146532808X270644.

-

Berti A, Bregani ER, Manenti F, Pizzi C: Outcome of severely malnourished children treated co-ordinate to UNICEF 2004 guidelines: a ane-year experience in a zone hospital in rural Federal democratic republic of ethiopia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008, 102 (nine): 939-944. x.1016/j.trstmh.2008.05.013.

-

Maitland 1000, Berkley JA, Shebbe Thou, Peshu N, English M, Newton CR: Children with severe malnutrition: tin those at highest risk of death exist identified with the WHO protocol?. PLos Med. 2006, 3 (12): e500-10.1371/journal.pmed.0030500.

-

Hossain MM, Hassan MQ, Rahman MH, Kabir ARML, Hannan AH, Rahman AKMF: Hospital direction of severely malnourished children: comparison of locally adjusted protocol with WHO protocol. Indian Pediatr. 2009, 46 (3): 213-217.

-

Ashworth A, Chopra G, McCoy D, Sanders D, Jackson D, Karaolis N, Sogaula N, Schofield C: WHO guidelines for management of severe malnutrition in rural South African hospitals: result on case fatality and the influence of operational factors. Lancet. 2004, 363 (9415): 1110-1115. x.1016/S0140-6736(04)15894-seven.

-

Ahmed T, Ali One thousand, Ullah MM, Choudhury Ia, Haque ME, Salam Ma, Rabbani GH, Suskind RM, Fuchs GJ: Mortality in severely malnourished children with diarrhoea and utilise of a standardised management protocol. Lancet. 1999, 353 (9168): 1919-1922. ten.1016/S0140-6736(98)07499-6.

-

Fergusson P, Chinkhumba J, Grijalva-Eternod C, Banda T, Mkangama C, Tomkins A: Nutritional recovery in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected children with severe acute malnutrition. Arch Dis Kid. 2009, 94 (7): 512-516. 10.1136/adc.2008.142646.

-

Chinkhumba J, Tomkins A, Banda T, Mkangama C, Fergusson P: The touch of HIV on mortality during in-patient rehabilitation of severely malnourished children in Malawi. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008, 102 (7): 639-644. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.04.028.

-

Manary MJ, Brewster DR: Intensive nursing care of kwashiorkor in Malawi. Acta Paediatr. 2000, 89 (2): 203-207. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2000.tb01217.10.

-

Khanum Southward, Ashworth A, Huttly SR: Growth, morbidity, and mortality of children in Dhaka later on handling for astringent malnutrition: a prospective study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998, 67 (5): 940-945.

-

Khanum S, Ashworth A, Huttly SR: Controlled trial of iii approaches to the treatment of severe malnutrition. Lancet. 1994, 344 (8939-8940): 1728-1732. x.1016/S0140-6736(94)92885-1.

-

Karaolis N, Jackson D, Ashworth A, Sanders D, Sogaula N, McCoy D, Chopra K, Schofield C: WHO guidelines for severe malnutrition: are they feasible in rural African hospitals?. Arch Dis Kid. 2007, 92 (3): 198-204. 10.1136/adc.2005.087346.

-

Puoane T, Cuming K, Sanders D, Ashworth A: Why do some hospitals achieve better intendance of severely malnourished children than others? Five-twelvemonth follow-up of rural hospitals in Eastern Cape, South Africa. Wellness Policy Plan. 2008, 23 (6): 428-437. ten.1093/heapol/czn036.

-

Ackatia-Armah RS, McDonald C, Doumbia S, Brown KH: Effect of selected dietary regimens on recovery from moderate acute malnutrition in young Malian children. Faseb J. 2012, 26:

-

Karakochuk C, Stephens D, Zlotkin S: Treatment of moderate acute malnutrition with fix-to-use supplementary nutrient results in college overall recovery rates compared with a corn-soya blend in children in southern Ethiopia : an operations. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012, 96 (4): 911-916. x.3945/ajcn.111.029744.

-

LaGrone LN, Trehan I, Meuli GJ, Wang RJ, Thakwalakwa C, Maleta K, Manary MJ: A novel fortified composite flour, corn-soy blend "plus-plus," is non inferior to lipid-based fix-to-use supplementary foods for the handling of moderate astute malnutrition in Malawian children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012, 95 (1): 212-219. 10.3945/ajcn.111.022525.

-

Matilsky DK, Maleta K, Castleman T, Manary MJ: Supplementary feeding with fortified spreads results in college recovery rates than with a corn/soy alloy in moderately wasted children. J Nutr. 2009, 139 (4): 773-778. 10.3945/jn.108.104018.

-

Nackers F, Broillet F, Oumarou D, Djibo A, Gaboulaud Five, Guerin PJ, Rusch B, Grais RF, Captier V: Effectiveness of set up-to-use therapeutic nutrient compared to a corn/soy-blend-based pre-mix for the treatment of childhood moderate astute malnutrition in Niger. J Trop Pediatr. 2010, 56 (6): 407-413. ten.1093/tropej/fmq019.

-

Diop EI, Dossou NI, Briend A, Yaya MA, Ndour MM, Wade S: Home-based rehabilitation for severely malnourished children using locally made Ready-to-Employ Therapeutic Nutrient (RTUF). Pediatric Gastroenterology 2004. 2004, Bologna: Medimond Publishing Co, 101-105. edn

-

Sandige H, Ndekha MJ, Briend A, Ashorn P, Manary MJ: Habitation-based handling of malnourished Malawian children with locally produced or imported gear up-to-use food. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004, 39 (2): 141-146. 10.1097/00005176-200408000-00003.

-

Chapko MK, Prual A, Gamatie Y, Maazou AA: Randomized Clinical-Trial Comparison Hospital to Ambulatory Rehabilitation of Malnourished Children in Niger. J Trop Pediatr. 1994, 40 (4): 225-230. 10.1093/tropej/twoscore.4.225.

-

Oakley Eastward, Reinking J, Sandige H, Trehan I, Kennedy G, Maleta Thousand, Manary One thousand: A set-to-use therapeutic food containing 10% milk is less effective than one with 25% milk in the handling of severely malnourished children. J Nutr. 2010, 140 (12): 2248-2252. 10.3945/jn.110.123828.

-

Diop EHI, Dossou NI, Ndour MM, Briend A, Wade S: Comparison of the efficacy of a solid ready-to-use food and a liquid, milk-based diet for the rehabilitation of severely malnourished children: a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003, 78 (ii): 302-307.

-

Branger B, Cadudal JL, Delobel Yard, Ouoba H, Yameogo P, Ouedraogo D, Guerin D, Valea A, Zombre C, Ancel P: Spiruline equally a food supplement in case of infant malnutrition in Burkina-Faso. [French] La spiruline comme complement alimentaire dans la malnutrition du nourrisson au Burkina-Faso. Curvation Pediatr. 2003, 10 (five): 424-431. 10.1016/S0929-693X(03)00091-5.

-

Navarro-Colorado C: Clinical trial of BP100 vs F100 milk for rehabilitation of severe malnutrition. Field Exchange. 2005, v (24): 22-27.

-

Kerac M, Bunin J, Seal A, Thindwa M, Tomkins A, Sadler Grand, Bahwere P, Collins South: Probiotics and prebiotics for severe acute malnutrition (PRONUT study): a double-blind efficacy randomised controlled trial in Malawi. Lancet. 2009, 374 (9684): 136-144. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60884-9.

-

Fauveau C, Siddiqui M, Briend A, Silimperi DR, Begum N, Fauveau V: Limited impact of a targeted food supplementation program in Bangladeshi urban slum children. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1992, 12 (1): 41-46.

-

Trehan I, Goldbach HS, LaGrone LN, Meuli GJ, Wang RJ, Maleta KM, Manary MJ: Antibiotics as part of the management of severe acute malnutrition. N Engl J Med. 2013, 368 (5): 425-435. ten.1056/NEJMoa1202851.

-

Hsu CC: The Delphi Technique: Making Sense of Consensus. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation. 2007, 12 (10): 1-viii.

-

WHO: Severe malnutrition: Report of a consultation to review current literature, half dozen-7 September 2004. 2005, Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Arrangement

-

Collins S, Sadler K, Dent N, Khara T, Guerrero Southward, Myatt 1000, Saboya M, Walsh A: Key bug in the success of community-based management of severe malnutrition. Nutrient Nutr Bull. 2006, 27 (3 Suppl): S49-82.

-

Hall A, Blankson B, Shoham J: The impact and effectiveness of emergency diet and diet related interventions: a review of published prove 2004-2010. 2011, Oxford, UK: Emergency Nutrition Network

-

Khara T, Collins S: Special Supplement: Community-based Therapeutic Care (CTC). 2004, Concern Worldwide and Valid International

-

Fergusson P, Tomkins A: HIV prevalence and mortality amongst children undergoing treatment for severe astute malnutrition in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009, 103 (6): 541-548. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.x.029.

-

Heikens GT, Bunn J, Amadi B, Manary M, Chhagan M, Berkley JA, Rollins N, Kelly P, Adamczick C, Maitland K, et al: Case management of HIV-infected severely malnourished children: challenges in the area of highest prevalence. Lancet. 2008, 371 (9620): 1305-1307. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60565-6.

-

Maleta K, K J, D MB, B A, Grand M, W J, Thou T, A P: Supplementary feeding of underweight, stunted Malawian children with a ready-to-apply food. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004, 38 (2): 152-158. 10.1097/00005176-200402000-00010.

-

Galpin 50, Thakwalakwa C, Phuka J, Ashorn P, Maleta M, Wong WW, Manary MJ: Chest milk intake is non reduced more than past the introduction of free energy dense complementary food than by typical infant porridge. J Nutr. 2007, 137 (vii): 1828-1833.

-

Phuka J, Thakwalakwa C, Maleta K, Cheung YB, Briend A, Manary Grand, Ashorn P: Supplementary feeding with fortified spread among moderately underweight half dozen-18-calendar month-old rural Malawian children. Matern Child Nutr. 2009, 5 (two): 159-170. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2008.00162.10.

-

Mates E, Deconinck H, Guerrero S, Rahman South, Corbett M: Interagency Review of Selective Feeding Programs in South, North and Westward Darfur States, Sudan, March 8 - April ten, 2008. 2009, Washington D. C. : Food and Nutrition Technical Assist Ii Project

-

Ndekha MJ, Oosterhout JJ, Zijlstra EE, Manary One thousand, Saloojee H, Manary MJ: Supplementary feeding with either set-to-use fortified spread or corn-soy blend in wasted adults starting antiretroviral therapy in Malawi: randomised, investigator blinded, controlled trial. BMJ. 2009, 338: b1867-10.1136/bmj.b1867.

-

Flax VL, Thakwalakwa C, Phuka J, Ashorn U, Cheung YB, Maleta K, Ashorn P: Malawian mothers' attitudes towards the use of two supplementary foods for moderately malnourished children. Appetite. 2009, 53 (2): 195-202. 10.1016/j.appet.2009.06.008.

-

Chang CY, Trehan I, Wang RJ, Thakwalakwa C, Maleta Grand, Deitchler G, Manary MJ: Children successfully treated for moderate acute malnutrition remain at risk for malnutrition and death in the subsequent year after recovery. J Nutr. 2013, 143 (2): 215-220. 10.3945/jn.112.168047.

-

Briend A, Prinzo ZW: Dietary management of moderate malnutrition: time for a modify. Food Nutr Bull. 2009, thirty (3 (Suppl)): S265-S266.

-

Gross R, Webb P: Wasting time for wasted children: severe child undernutrition must be resolved in non-emergency settings. Lancet. 2006, 367 (9517): 1209-1211. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68509-7.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Cheri Nickel for her help developing the search strategies; Robert Ackatia-Armah, El Hadji Issakha Diop and Mark Manary for providing boosted information on the studies included in this review; Muttaquina Hossain for her contributions to screening; Jay Berkley, Marko Kerac, Marzia Lazzerini, Cecile Salpeteur and others for their insight and participation in the Delphi process.

Declarations

The publication costs for this supplement were funded by a grant from the Beak & Melinda Gates Foundation to the US Fund for UNICEF (grant 43386 to "Promote evidence-based decision making in designing maternal, neonatal, and child health interventions in depression- and middle-income countries"). The Supplement Editor is the principal investigator and atomic number 82 in the development of the Lives Saved Tool (List), supported by grant 43386. He declares that he has no competing interests.

This article has been published as office of BMC Public Health Volume thirteen Supplement 3, 2013: The Lives Saved Tool in 2013: new capabilities and applications. The full contents of the supplement are available online at http://www.biomedcentral.com/bmcpublichealth/supplements/13/S3.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

LML and ZAB conceptualized the review and analysis. LML led the systematic review and Delphi process and wrote the manuscript with substantial inputs from Pow and ZAB. KW was involved in abstraction, analysis, Delphi and writing the first manuscript draft. PW and TA significantly contributed throughout the stages of the review and manuscript preparation.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Electronic supplementary textile

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This commodity is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/two.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Artistic Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/one.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lenters, L.Chiliad., Wazny, K., Webb, P. et al. Treatment of severe and moderate acute malnutrition in low- and center-income settings: a systematic review, meta-assay and Delphi process. BMC Public Wellness 13, S23 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-xiii-S3-S23

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-thirteen-S3-S23

Keywords

- Food Insecurity

- Example Fatality Rate

- Severe Acute Malnutrition

- Delphi Process

- Acute Malnutrition

Source: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-13-S3-S23

0 Response to "Treatment of Sam and Mam in Low- and Middle-income Settings a Systematic Review"

Postar um comentário